1

COMMUNICATION

Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God. (Colossians 3:16)

And do not get drunk with wine, for that is debauchery, but be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart, giving thanks always and for everything to God the Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, submitting to one another out of reverence for Christ. (Ephesians 5:18–21)

Here are the Bible’s most developed commands to sing. The Apostle Paul sets norms for the nature, function, and content of congregational singing, which, when interpreted in the light of the rest of Scripture, provide the basis for a biblical theology of church music. While he does not use a word for “congregation” or “assembly,” we know he is describing corporate worship, because he speaks of the word of Christ operating on a particular group of believers in Colossae or Ephesus through their teaching, hymns, and singing to God. Such worship might occur privately, but it certainly also occurred publicly (1 Cor. 14:26), which means we must take the passages as instructional on public worship (although they may also apply to Christian song outside of called worship services). Given God’s zeal for his own worship, we should not be surprised to find these clear instructions directed to this element of it. The surprising thing would be if Scripture were silent on the matter.

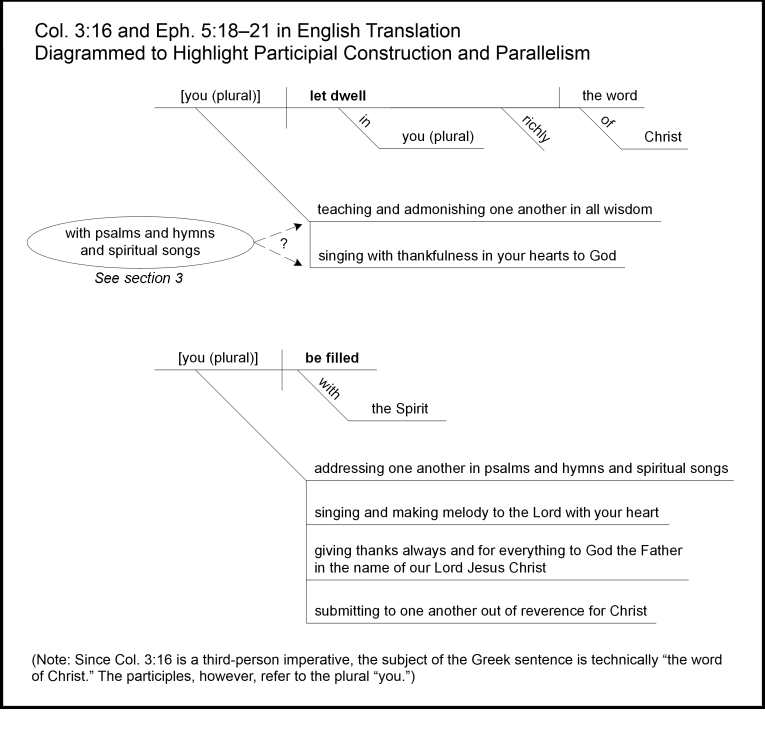

Both passages appear midway through the paraenesis section of an epistle and are largely parallel in structure and sense, each with an imperative (“let the word of Christ dwell in you richly” and “be filled with the Spirit”) followed by a series of participles (teaching, admonishing, and singing; addressing, singing, making melody, giving thanks, and submitting). This structure can perhaps most swiftly be grasped if diagrammed.

With the exception of the last participial phrase in the Ephesians passage (v. 21, which serves as a transition to Paul’s exhortation regarding submission in 5:22–6:9) every phrase has its counterpart in the other passage. The third participial phrase in the Ephesians passage, “giving thanks,” expands on the prepositional phrase “with thankfulness” found in Colossians. Likewise the prepositional phrase “in all wisdom” found in Colossians corresponds to Paul’s overarching theme in the Ephesians passage: “Look carefully then how you walk, not as unwise but as wise” (Eph. 5:15). Clearly, Paul’s wording in one passage can be compared to his wording in the other to improve our understanding.

The words that have attracted the most attention are, of course, “psalms and hymns and spiritual songs,” since they seem to designate particular repertoires that Paul authorizes the early church to sing. But the words defy interpretation. Some conclude that, since Paul uses three different terms, he at least intends the church to sing a variety of types from different sources. But this is to overlook the possibility that he, rather than distinguishing between types, might be piling up synonyms to emphasize the richness of the Word’s indwelling and the Spirit’s filling. Such a rhetorical device is common in the Scriptures, as in “signs and wonders and mighty works.” Others conclude that “psalm,” “hymn,” and “song” (ode) all refer to canonical psalms, because the Septuagint used these terms to translate generic designations in the Book of Psalms, and because “spiritual” means “inspired.” But this reads too much into the Septuagint’s use of the terms. Rather than transliterating musico-liturgical terms as they appear in the Hebrew Book of Psalms, the Greek translation employs common Greek words that may or may not correlate to the meaning of the Hebrew. In ancient Greek literature, “ode” is the most common word for vocal music, and “hymn” is the most common word for a song of praise. First-century Greek-speaking believers would likely have used these words to refer to many things besides just psalms.[1] Today’s exclusive psalmist argues that the Septuagint’s terms, in the context of a description of church music, must denote canonical psalms; but the Septuagint’s terms are so basic to first-century musical vocabulary that, by the same argument, almost any description of sung praise will be taken as indicating canonical psalms, for it will probably use these terms. One wonders which terms exclusive psalmists would expect Paul to use had he not meant to specify canonical psalms.[2] Whereas, if he did mean to specify them, it seems he could have done so unambiguously by mentioning David or the Book of Psalms. Nor does the qualification that the songs be spiritual (pneumatikos) necessarily mean that they were inspired. No major commentator insists on this, for, as Charles Hodge put it, “not only inspired men are said to be filled with the Spirit, but all those who in their ordinary thoughts and feelings are governed by the Holy Ghost.”[3] Paul’s list of musical or poetic terms tells us surprisingly little about singing in worship.

But the verses that include the list, when read in their entirety, do. Namely, they tell us what we should sing, to whom we should sing, and how we should sing. We are to sing the word of Christ; we are to sing it to one another[4] and to God; and each is to do this with his heart. Subsequent sections of the “Biblical Model” part of this website will consider each of these points in turn, but notice must first be taken of an assumption Paul makes concerning the function of music in worship. Until we see how this differs from some modern Western notions, we are liable to draw false inferences from the text. According to Paul, why do we sing in worship? To communicate. He sees singing as a medium through which we teach, admonish, and address one another, and through which we convey gratitude to God, and Paul does so, we must conclude, because he sees singing as a particularly effective medium for such communication.

Why he sees it this way, the Bible does not say. We sing because God tells us to, and we know he has his reasons. For some sense of what those reasons might be, we can study his general revelation to identify properties in music that support the kind of congregational communication described by Paul and exemplified elsewhere in Scripture. First, we know that the clearest and most graceful way for multiple voices to speak together is via musical tone and rhythm. Second, we know that music is one of the most powerful aids to human memory, a faculty which congregants must use, if the word of Christ is to dwell in them richly (see section 4). Third, musical structures can complement, and even enhance, the syntactical and poetic structure of sung text. Fourth, the sonic order of music appeals to the imagination as a manifestation of the Creator’s glory and, as such, constitutes the ultimate adornment of glorifying speech, used by all human societies to communicate the weightiness of certain statements.

Other Purposes

By contrast, ask a representative sampling of modern Westerners why music matters to them, and you will hear quite different ideas. You will hear that the purpose of music is either to provide aesthetic pleasure or to express and arouse emotions. We like music because we delight in its form. And we like music for the emotional experiences it provides. For all we know, the Apostle Paul might very well have liked it for those same reasons when he heard concerts emanating from Greek theaters as he passed them on the street (if he ever passed them on the street), but such is not the music he describes here, and these are not the purposes he assigns to church music. It does not occur to the modern that music could ever have but one or the other of our two pet purposes for it. Yet to evaluate church music on the basis of the modern’s aesthetic values would be unbiblical, because the Bible assigns a different purpose to church music: to provide a vehicle by which congregants can communicate to God and to one another.

If we approach church music expecting to encounter musical thrills, then the kind of music to which our forebears corporately worshiped will offend us, not merely because it is old-fashioned but because, in a certain sense, it actually is less musical than the various (classical and popular) repertoires that evolved as objects for aesthetic enjoyment. In particular, congregational song—with its rhythmic simplicity, unrefined timbres, and neglect of instruments—will offend those who go to church for the music. It will seem out of tune, outdated, and boring. The beauty of an object is, after all, its formal effectiveness, and if we try to employ the object for a purpose other than that for which it was intended, the results will likely disappoint. In the best traditions of congregational singing the music is very beautiful indeed, not as an object of purely musical value, but rather as effective support for the proclamation of what ought to be proclaimed.

The other inclination noted above, to treat church music as a kind of emotional stimulus, is likewise at odds with traditional hymnody. If we expect church music, as music, to make us feel emotionally alive, then the tune of “Oh, for a Thousand Tongues to Sing,” compared to what plays on one’s ipod, will seem lifeless, its text doctrinal and distracting. Treating church music as an emotional stimulus seems commonsensical and unassailably biblical to many Christians, since poetry and music are widely believed to be “about emotion,”[5] and in English translations of the Old Testament God’s people are frequently said to “sing for joy” and to “make a joyful noise.” Augustine defended the practice of singing in church on the basis that it “is so effective in stirring the soul with piety and in kindling the sentiment of divine love.”[6] Even church musicians commonly see their work as supplying the emotive element in worship. Lowell Mason himself, arguably the greatest church musician in American history, wrote, “The song is in its nature emotional. . . . To express our feelings, then, and of course our religious feelings, is the object of song in worship.”[7]

To think clearly about the role of emotion in poetry and music, it is critical that we distinguish between, on one hand, singing from emotion or responding emotionally to a song’s message and, on the other, singing to express emotion or to induce emotion. The one kind of singing has an emotional context, the other is actually an emotional song. When a song has an emotional context, it communicates something that flows from, or leads to, emotion. When a song is essentially emotional, its poetic and musical form is designed to communicate emotion itself. Emotion is incidental to the one and intrinsic to the other. An example of music with an emotional context would be when ordinary people sing their national anthem. The song enables them to voice their dedication to the population and principles of the country, and such dedication naturally engages the emotions, but there is nothing in the structure or performance of the song that is emotional per se. Rather, one emotes in response to the importance and beauty of what is said. Another example would be Christmas caroling, which, although it lacks any marks of what typically passes for emotional music, nevertheless can move us deeply when the singing effectively communicates a message of vital importance. By contrast, an example of essentially emotional music would be the background scoring of a movie or political advertisement. We use such music to generate prescribed emotions, not to communicate a discursive message. Thus our spirits lift at the happy ending when we hear the “happy” music. We sense that the politician’s opponent is dangerous when we hear the “sinister” music. Emotional music can easily privilege a semblance of emotion over truth and the true emotions associated with it, and when that happens we call it sentimentality. The cart has gotten in front of the horse. Then, reality and meaning will generally be kept to a minimum, since such things merely get in the way by demanding repentance or reflection, or by otherwise distracting us from the immediacy of feeling that we seek in emotional music.[8]

The music of biblical worship certainly is associated with strong emotions. While it seems safe to assume that some of these emotions were negative (for example, Mishnah Tamid says that the laments in Psalms 81–82 were sung at the daily sacrifice in the Temple on Thursdays and Tuesdays, respectively) the Bible never actually states that they were. Biblical descriptions of singing in worship always associate it with joy.

And Jehoiada posted watchmen for the house of the LORD under the direction of the Levitical priests and the Levites whom David had organized to be in charge of the house of the LORD, to offer burnt offerings to the LORD, as it is written in the Law of Moses, with rejoicing and with singing, according to the order of David. (2 Chr. 23:18)

Sing to God, sing praises to his name;

lift up a song to him who rides through the deserts;

his name is the LORD;

exult before him! (Ps. 68:4)

See also Nehemiah 12:27 and Psalm 9:2, as well as many other passages. Psalm 137 even suggests that it is impossible or inappropriate to sing the songs of Zion without joy.

Yet the concurrence of music and emotion does not necessarily mean that the music expresses or induces the emotion. With surprisingly few exceptions the Bible merely associates the music of worship with emotion and does not describe it as being emotional. We do not, for example, read of anyone in the congregation “singing their joy” or “singing to increase their joy.” Nor do we find Hebrew words for music grammatically combined with words for emotion in descriptions of corporate worship. That is, the rejoicing and the singing occur simultaneously or are linked poetically by parallelism, but we do not find Hebrew expressions that suggest what, in English, we would call “joyful music” (1 Chr. 15:16 and Ezra 3:12–13 being the only clear exceptions). The words rānan and rwʽ, which the ESV renders “to sing for joy” and “to make a joyful noise” (e.g., Ps. 5:11; 95:1), mean “to shout” and “to raise a noise” and can be associated with glad, distressed, or aggressive states of mind according to the context. When translators add the phrase “for joy” or the adjective “joyful” in contexts of corporate worship, they are paraphrasing. The people raising the shout or noise are certainly joyful, but the text does not characterize the music itself as being joyful. Perhaps rānan, rwʽ and their derivatives refer to the congregation’s simple acclamations, such as “hallelujah” or “for his steadfast love endures forever,” as opposed to the more musical šîr and zmr (meaning “to sing” and “to make music of praise”) performed by particular musicians.[9]

If the Bible’s disregard for the emotive characteristics of music in worship seems counterintuitive to us, we may be bringing to our reading of these passages certain assumptions about music that we know to be valid in other musical situations (1 Samuel 16:23; Job 21:12). Certainly we would not be the first to do so. We are heirs to two thousand years of reflection on these passages that has been shaped by the ancient Greek and modern Western doctrine of musical ethos: the belief that music imitates human passions and that hearers are thereby imbued with those passions.[10] Regardless of the propriety of importing such a psychological view of music to our reading of these passages, there can be no doubt that the emphasis of the Bible itself lies elsewhere.

Conclusion

The salient point in almost all biblical allusions to music in corporate worship is that someone is saying something to someone.

Sing praises to the LORD, who sits enthroned in Zion!

Tell among the peoples his deeds! (Ps. 9:11)

Be exalted, O LORD, in your strength!

We will sing and praise your power. (Ps. 21:13)

Shout for joy to God, all the earth;

Sing the glory of his name;

give to him glorious praise! (Ps. 66:1–2)

We give thanks to you, O God;

we give thanks, for your name is near.

We recount your wondrous deeds. . . .

I will declare it forever;

I will sing praises to the God of Jacob. (Ps. 75:1, 9)

Oh sing to the LORD a new song;

sing to the LORD, all the earth!

Sing to the LORD, bless his name;

tell of his salvation from day to day. (Ps. 96:1–2)

One generation shall commend your works to another,

and shall declare your mighty acts. . . .

They shall pour forth the fame of your abundant goodness

and shall sing aloud of your righteousness. (Ps. 145:4, 7)

Therefore, one who speaks in a tongue should pray for the power to interpret. For if I pray in a tongue, my spirit prays but my mind is unfruitful. What am I to do? I will pray with my spirit, but I will pray with my mind also; I will sing praise with my spirit, but I will sing with my mind also. Otherwise, if you give thanks with your spirit, how can anyone in the position of an outsider say “Amen” to your thanksgiving when he does not know what you are saying? For you may be giving thanks well enough, but the other person is not being built up. (1 Cor. 14:13–17)

I will tell of your name to my brothers;

in the midst of the congregation I will sing your praise. (Heb. 2:12)

The one who sings in the congregation praises and thanks God; he tells of God’s deeds, power, glory, and salvation; and, in so doing, he is always addressing someone: God, his fellow worshipers, or sometimes even himself in a kind of self-summons to praise. The clear injunction of Colossians 3:16 and Ephesians 5:18–21 and the example set by scores of biblical references to music in corporate worship teach us that its function is to communicate. The fulfillment of this function depends on three things: the substance and clarity of the message, the identity of the intended hearers, and the worshiper’s sincerity. These are the biblical criteria for judging church music.

Such judgment does not preclude the appearance of musical beauty or musical emotivity, but where they appear, given their inconspicuousness in Scripture’s descriptions of church music, they would seem to be means to an end and not the reason we sing. We sing to communicate, not to feel a certain way. Yet when we follow the biblical model, our church music will in fact be the most beautiful and astonishingly emotional. The music will be beautiful precisely for the way it helps to convey the message of who God is and what he has done, and the emotions will be all the more robust for being a response to the reality of that message. Surely this is part of what it means to teach and admonish “in all wisdom” as Paul puts it in Colossians 3:16—indeed, part of what it means to walk in wisdom and be filled with the Spirit, which is Paul’s great theme in Ephesians 5:15–6:9.

Continue to section 2, “Message.”NOTES

[1] Even within the Septuagint “psalm,” “hymn,” and “ode” are used to translate many different Hebrew words, sometimes interchangeably. Likewise, these Greek terms are used throughout the writings of hellenized Judaism in reference to many kinds of songs, not just canonical psalms. J. A. Smith, “First-Century Christian Singing and Its Relationship to Contemporary Jewish Religious Song,” Music & Letters 75 (1994): 8.

[2] Exclusive psalmists may answer that Paul didn’t have to specify what he meant, as psalms were supposedly the only songs used in Old Testament corporate worship, and therefore his original readers would assume them here. We would question the premise of this claim. Although psalms certainly figured prominently in Old Testament worship, there is hardly enough evidence for us to conclude that they were sung exclusively. In fact, 1 Chronicles 16—the only passage in the Old Testament besides Psalm 30 that unequivocally identifes a song for use in tabernacle or temple—cites not a psalm but a hymn based on parts of three different psalms (unless the hymn came first, in which case the psalms were based on the hymn). The superscriptions of many Psalms name levitical authors or include terms believed to be liturgical, but if we take these as proof of temple usage, we must do the same for Habakkuk 3.

[3] Charles Hodge, A Commentary on Ephesians (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1964), 222.

[4] The pronoun in the phrases “teaching and admonishing one another” and “addressing one another” is reflexive (heautois) rather than reciprocal (allēlōn). Literally, Paul says “teaching and admonishing yourselves.” Use of the plural reflexive pronoun to indicate reciprocity is unusual but not rare in New Testament Greek. See, for example, the preceding injunction to forgive one another (heautois) in Col. 3:13 and Eph. 4:32.

[5] One even finds poets and professors of literature who claim this. For example, Jeanne Murray Walker, “On Poets and Poetry,” in The Christian Imagination, ed. Leland Ryken (Colorado Springs: Shaw Books, 2002), 371.

[6] Augustine Letter 55 18.34.

[7] Lowell Mason, Song in Worship: An Address (Boston: printed for private circulation, 1878), 6–7.

[8] For a particularly insightful (and concise) explanation of sentimentality in music, see Roger Scruton, The Aesthetics of Music (Oxford University Press, 1997), 485–88.

[9] See Ezra 3:10–13; Ps. 149:1, 5; and Sirach 50:18–19.

[10] Plato Laws 2.665–70C and Aristotle Politics 8.1340a–b.